Boise State University Boise State University

ScholarWorks ScholarWorks

Educational Technology Faculty Publications

and Presentations

Department of Educational Technology

5-2020

Guidelines for Designing Online Courses for Mobile Devices Guidelines for Designing Online Courses for Mobile Devices

Sally J. Baldwin

Boise State University

Yu-Hui Ching

Boise State University

Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.boisestate.edu/edtech_facpubs

Part of the Instructional Media Design Commons, and the Online and Distance Education Commons

Publication Information Publication Information

Baldwin, Sally J. and Ching, Yu-Hui. (2020). "Guidelines for Designing Online Courses for Mobile Devices".

TechTrends: Linking Research & Practice to Improve Learning,

64

(3), 413-422. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/

s11528-019-00463-6

This is a post-peer-review, pre-copyedit version of an article published in

TechTrends: Linking Research & Practice

to Improve Learning

. The Anal authenticated version is available online at doi: 10.1007/s11528-019-00463-6

1

This is an author-produced, peer-reviewed version of this article. The final, definitive version of this document can be found online at

TechTrends: Linking Research & Practice to Improve Learning, published by Springer. Copyright restrictions may apply. doi: 10.1007/s11528-

019-00463-6

Guidelines for Designing Online Courses for Mobile Devices

Sally J. Baldwin

Boise State University

Yu-Hui Ching

Boise State University

Abstract

College students frequently use mobile devices (e.g., smartphones and tablets) to access online

courses yet online course designers often do not design courses with mobile learning in mind.

This research identified seven national and statewide online course design evaluation

instruments and examined the criteria that guide course designers designing online courses for

learning with mobile devices. Currently, minimal guidance on course design for mobile learning

is offered in most of the national and statewide online course design instruments. Research-

supported design tips that promote device compatibility, content readability, format

optimization, and mobile-friendly navigation are suggested in this paper to guide future online

courses design for mobile delivery.

Introduction

The EDUCAUSE Horizon Report 2019 Higher Education Edition identifies mobile learning as one of the most

important developments in online learning (Alexander et al., 2019). Mobile learning is typically defined as an ability

to learn anywhere, any time through the use of mobile computing devices (e.g., smartphones, tablets, and laptops;

EDUCAUSE, 2019). Research indicates that most college students have mobile devices. For example, a survey of

college students (N=64,536), from 130 higher educational institutions, found that practically all college and university

students (95 %) have smartphones (Galanek et al., 2018). A 2016 survey of 1,474 University of Central Florida (UCF)

students revealed that 99 percent of the respondents owned a smartphone and 63 percent owned a tablet (Seilhamer et

al., 2018a).

College students are using mobile devices for their educational pursuits. A 2018 survey of 1,500 online undergraduate

and graduate students discovered 67 percent of online students conducted some or all of their course work on their

mobile device (Magda & Aslanian, 2018). And, even though 91 percent of college students own laptop computers

(Galanek et al., 2018), college students may choose to leave their laptops at home, mainly because they find it

cumbersome to carry a laptop (Kobus et al., 2013) and worry about theft (Attenborough & Abbott, 2018; Kobus et al.,

2013). Smaller mobile devices (e.g., smartphones and tablets) are portable, easy to use, provide relatively strong

computing power, and offer web access (Attenborough & Abbott, 2018; Hsu & Ching, 2012; Viberg & Grönlund,

2017). Students value the portability of mobile devices and the ability to work any place and any time. In 2018, the

University of Central Florida (UCF) surveyed students (N=4,134) and similarly found 99.8 percent of students owned

mobile devices, and 86 percent of students use the Canvas Mobile app to access online courses (Seilhamer et al.,

2018b). This paper is focused on the use of smaller mobile devices (smartphones and tablets) to access online courses

that have been built within learning management systems (LMS).

Accessing learning on mobile devices presents challenges to students. Researchers surveyed university students

(N=252) and found that even though all of the surveyed students used mobile phones to access the LMS, the students

expressed concern over the LMS limitations and felt courses were cluttered on small screens (Hu et al., 2016). The

smaller screen size can create usability limitations for students attempting to complete course work. As a result,

students often rely on their phones to complete easy, low-stake tasks through the LMS, such as retrieving and accessing

learning materials (Hu et al., 2016). In the past, LMSs were designed primarily for desktop and laptop use and were

“functionally limited in their potential to be accessed through mobile devices” (Viberg & Grönlund, 2017, p. 359). In

a study conducted to evaluate faculty (N=220) and students’ (N=181) experiences with Canvas LMS at a public higher

education institution, Wilcox at el. (2016) found that “faculty design their courses for delivery on laptops, but students

use smartphones to access Canvas” (p. 1163). Recently, LMS companies have been working towards improving the

functionality of their mobile applications (apps) (Alexander et al., 2019; Blackboard, 2019; Canvas, 2018c; Moodle,

2019) to address students’ needs.

2

Student use of mobile devices for online learning should be taken into account when online course designers design

course materials (Viberg & Grönlund, 2017). It is unclear what resources online course designers (instructors and

instructional designers) use to advise their design of mobile compatible courses; however, online course designers

may rely upon established course design evaluation instruments to guide the design and assess quality (Kleen & Soule

2010). This paper examines the national and statewide course design instruments to understand the guidance online

course designers are being provided on this important topic when designing or evaluating online courses.

Accessing Learning on Mobile Devices

Students find that using mobile devices is a convenient way to do certain online learning activities/tasks. For example,

students tend to use mobile phones for viewing timetables and notes (López & Silva, 2014; Seilhamer et al., 2018a),

accessing course readings (Asiimwe & Grönlund, 2015; Magda & Aslanian, 2018), checking course messages,

participating in course discussions and checking grades (Asiimwe & Grönlund, 2015; Magda & Aslanian, 2018;

Seilhamer et al., 2018a). There appears to be a correlation with the device size, pages viewed and time spent in the

system. Students using mobile devices visit less pages and spend less time in the system compared to students using

laptops or desktop computers (López & Silva, 2014; Mödritscher, Neumann, & Brauer, 2012; Seilhamer et al., 2018a).

Students using mobile phones are also apt to visit only one page on the site, before leaving it (López & Silva, 2014).

López and Silva (2014) suggested this may be a result of the small screen size of the device, or because students are

taking advantage of the portability of the device to get singular information (e.g., announcements). Test taking can

also be hampered on mobile devices. Research suggests that it takes longer to load pages and read questions on mobile

devices (Hwang & Tsai, 2011).

Despite user challenges, students express a strong desire to access the LMS via their mobile devices (Asiimwe &

Grönlund, 2015). Students tend to adopt mobile devices into their learning as a result of their positive attitudes toward

technology, which often correlates with general self-efficacy in technology, and an increased perceived usefulness of

mobile devices in their learning (Han & Shin, 2016). However, researchers cautioned that confidence and openness

towards mobile devices does not assure learning effectiveness (Joo et al. 2016; Shin & Kang, 2015) and stressed the

importance of positive support from instructors and institutions to increase the usefulness of mobile devices in online

learning.

Demographics also make a difference in the use of mobile devices. Galanek et al. (2018) found that smartphones were

owned by the vast majority of higher education students, yet “non-white, first-generation college students, students

whose families have lower incomes, and those with disabilities” (p. 11) viewed mobile devices as more important for

academic success than white, wealthier students. Twenty percent of the students Magda and Aslanian (2018) surveyed

completed all of their coursework on mobile devices. It is important that instructors realize students are accessing

online courses in this manner and design courses to meet the needs of students.

Mobile Devices and LMS

The U.S. higher education LMS market is dominated by Blackboard, Canvas, Desire2Learn (also known as

Brightspace, D2L), and Moodle, which account for 90.3 percent of institutions and 92.7 percent of student enrollment

(Edutechnica, 2019). These companies continue to improve their mobile-friendliness (Alexander et al., 2019). The

Blackboard app helps students complete coursework (Blackboard, 2019). And, a separate Blackboard Instructor app

allows instructors to view course content, grade assignments, connect with students in discussions, and interact with

the class in Blackboard Collaborate (Blackboard, 2018b). Also, Blackboard offers responsive themes (e.g., the Learn

2016 Theme, and Blackboard Ultra) that improve the learning experience for mobile users (Blackboard, 2018a;

2018c).

Canvas applications (i.e., apps) afford “a limited set of features on mobile, but the apps don't cover all Canvas

functionality” (Canvas, 2018c, para. 2). Canvas provides information on features for the Canvas Teacher Mobile app

and the Student Mobile app available for iOS and Android users (see https://s3.amazonaws.com/tr-

learncanvas/docs/Mobile_CanvasTeacher.pdf). Canvas also offers a Canvas Mobile Users Group to support mobile

learning and offers suggestions for mobile friendly design (Canvas, 2019). Desire to Learn (D2L) is designed to work

on mobile devices but some materials and resources work better or only on desktop/laptop computers (Brightspace,

2018). Moodle acknowledges that it is “increasingly important to ensure...courses are mobile friendly (Moodle, 2019,

para. 1). Students are encouraged to install the Moodle mobile app and instructors are provided tips for optimizing

course materials for those students using the app on mobile devices (Moodle, 2019).

This is an author-produced, peer-reviewed version of this article. The final, definitive version of this document can be found online at

TechTrends: Linking Research & Practice to Improve Learning, published by Springer. Copyright restrictions may apply. doi: 10.1007/s11528-

019-00463-6

3

Disconnect: Mobile Devices and Course Design

Although several LMSs have improved interface, navigation, and available features to be used on mobile devices,

there is still a disconnect when students use mobile devices to participate in online learning, primarily because

instructors and course designers may be unaware of how students view the course, how they navigate the course, and

how they use the course. Instructors design online courses based on what they know (i.e., face-to-face instruction),

through the process of assimilation (Baldwin, 2019). Designing courses that will be consumed via mobile devices—

which trends indicate a greater number of students do—adds a new layer of complexity to course design. It is not

enough to click on “student view” (an option in most LMS settings); instructors must also review the LMS mobile

app to understand the course from the student’s perspective when accessing course materials using a mobile app.

Wilcox et al. (2016) explained the problem: “Instructors are not designing their courses for the target platform used

by students: smartphones. As a result, students are not able to engage fully with the course content in the manner

envisioned by the instructor” (p. 1167).

The effectiveness of online learning varies according to how the online course is designed and taught (Jaggars & Xu,

2016). Liu, Chen, Sun, Wible, and Kuo (2010) found, “the greater the online learning experiences of users, the stronger

their intention to use an online learning community” (p. 603). Studies show a correlation between perceived usefulness

and user satisfaction in online learning (Asiimwe & Grönlund, 2015; Lee & Lehto, 2013). When students are

dissatisfied, they are less motivated to learn (Asiimwe & Grönlund, 2015). In a study surveying university students

(N=34) using mobile devices to access the LMS in an online course, students suggested a need for contents to be

optimized for small screens, chunked, with questions formulated to incur short answers, and multiple-choice

assessments (Bogdanović, Barać, Jovanić, Popović, & Radenković, 2014). While course delivery platforms should

not dictate the learning activities and assessment formats, it is critical that online course designers ensure that “the

student’s learning experience is equivalent regardless of the delivery platform” (Wilcox et al., 2016, p. 1168).

Online Course Design Evaluation Instruments

Online course design evaluation instruments have been created to help instructors design and assess quality (Baldwin

et al., 2018). These tools can be used to encourage improvement in online courses through course design consistency

and foster a dialogue about quality in online courses (Legon, 2015). This paper turns to national and statewide online

course design evaluation instruments to identify the guidance online course designers are being provided to design

online courses for mobile delivery. The following research questions guided our study:

• How do national and statewide online course design evaluation instruments address learning using

mobile devices?

• What do national and statewide online course design evaluation instruments identify as common

standards to guide the design of online courses for learning using mobile devices?

Method

Publicly available national and statewide online course design evaluation instruments are potential data sources for

this study. To be included, the online course design evaluation instrument had to be (a) used to evaluate higher

education online courses, (b) published or revised within the last five years, (c) used to support student success, (d)

used at the national or statewide level, and, (e) currently in use. Previously, a study reviewed six online course

evaluation instruments to understand common criteria for quality online course design (see Baldwin et al., 2018).

Since that time, Canvas (LMS) introduced a national course evaluation instrument (see Baldwin & Ching, 2019b).

The most updated copies of these potential instruments were obtained and reviewed. Based on the inclusion criteria,

we identified the following seven instruments for this study:

• Blackboard Exemplary Course Program Rubric (Blackboard; Blackboard, 2017b),

• Canvas Course Evaluation Checklist (CCEC; Canvas, 2018a),

• CVC-OEI Course Design Rubric (OEI; California Virtual Campus-Online Education Initiative, 2018),

• Open SUNY Course Quality Review Rubric (OSCQR; Online Learning Consortium, 2019b),

This is an author-produced, peer-reviewed version of this article. The final, definitive version of this document can be found online at

TechTrends: Linking Research & Practice to Improve Learning, published by Springer. Copyright restrictions may apply. doi: 10.1007/s11528-

019-00463-6

4

• Quality Learning and Teaching Instrument (QLT; California State University, 2019)

• Quality Matters Higher Education Rubric (QM; Quality Matters, 2018),

• Quality Online Course Initiative (QOCI; Illinois Online Network, 2018).

We reviewed these seven instruments that met our criteria to specifically examine if and how the instruments address

online course design for learning using mobile devices. Both researchers individually reviewed the selected

instruments, identified the standards related to mobile learning in each instrument, and analyzed mobile learning

related standards for commonality. We then discussed our analysis to reach agreement.

Findings

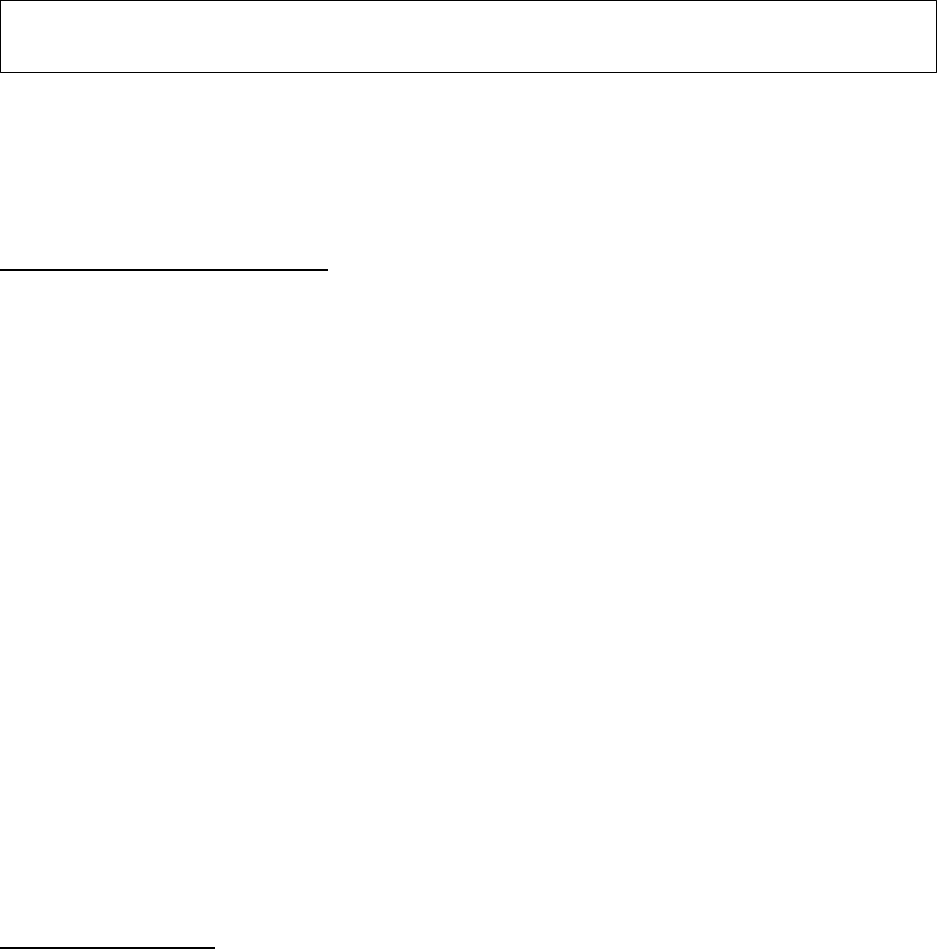

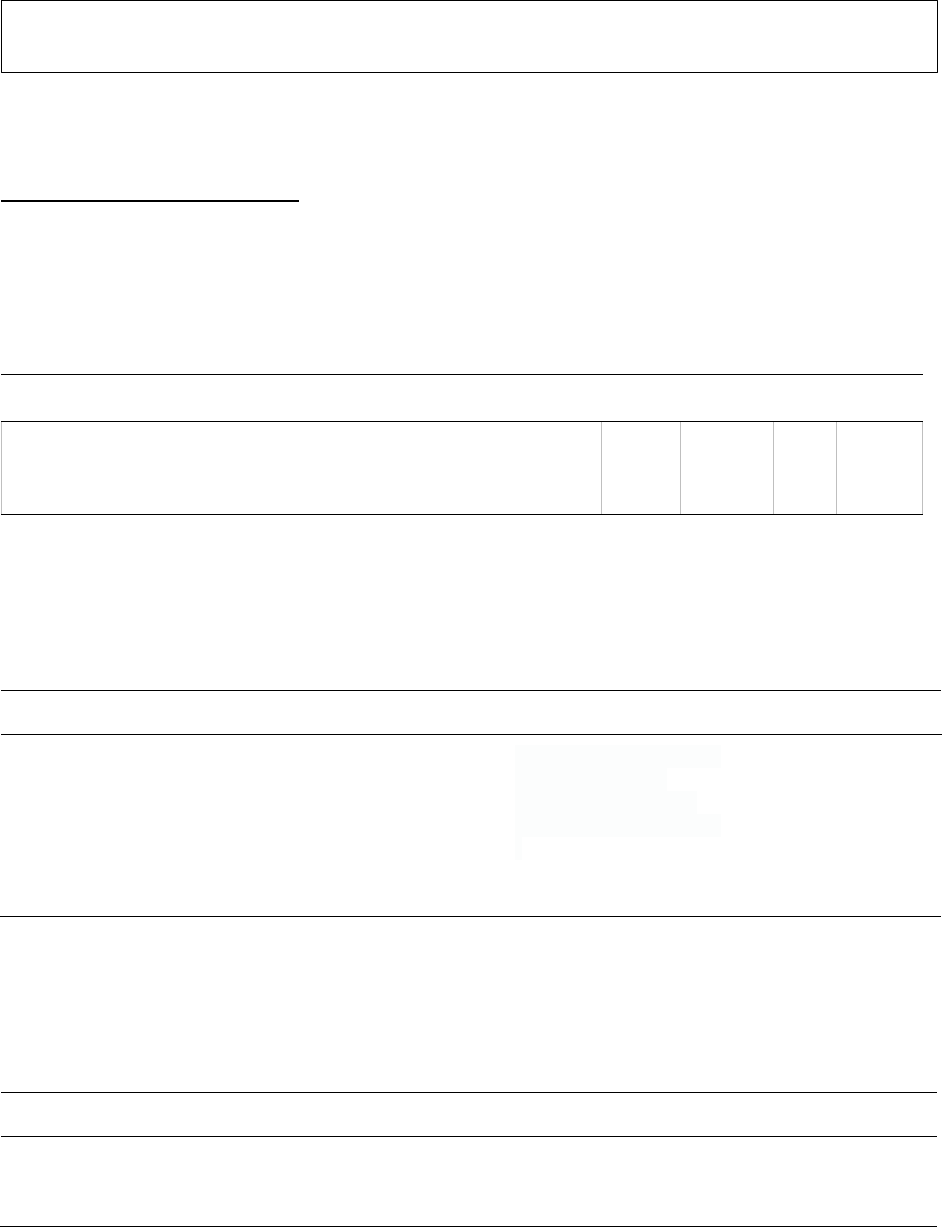

Table 1 presents the general characteristics of the seven selected national and statewide online course evaluation

instruments.

Table 1

Characteristics of Evaluation Instruments

Organization

Audience

Current

Version

Purpose

Is Mobile

Mentioned?

Blackboard

Blackboard LMS users

2017

Identify and disseminate best

practices for designing high quality

courses.

No

CCEC

Canvas LMS users

2018

To elevate the quality of Canvas

courses.

Yes

OEI

California Community

College online course

instructors &

instructional designers

2018

Establish standards to promote

student success and conforms to

existing regulations.

No

OSCQR

Instructors, peers, &

instructional designers

2018

To support online course quality

and continuous improvements to

the quality and accessibility of

online courses.

Yes

QLT

California State online

course instructors &

instructional designers

2017

To help design and evaluate quality

online teaching and learning.

Yes

QM

Course developers &

instructors

2018

Guide users through the

development, evaluation, and

improvement of online and blended

courses. Also, “certifies course as

meeting shared standards of best

practice”(Maryland Online, Inc.,

2014, slide 8).

No

QOCI

Higher education

faculty in the state of

Illinois

2018

To help colleges and universities

improve accountability of their

online courses by identifying best

practices and help the development

of quality online courses.

Yes

This is an author-produced, peer-reviewed version of this article. The final, definitive version of this document can be found online at

TechTrends: Linking Research & Practice to Improve Learning, published by Springer. Copyright restrictions may apply. doi: 10.1007/s11528-

019-00463-6

5

After analyzing the seven national and statewide online course design evaluation instruments, we found only four

instruments—CCEC, OSCQR, QLT, and QOCI—include guidelines for mobile learning. We discuss those guidelines

to understand how the instruments are directing online course designers.

Canvas Course Evaluation Checklist

The CCEC includes a “mobile device consideration” notation under four criteria. The two criteria that are noted as a

“mobile device consideration” and are deemed “essential and a standard design component” (Canvas, 2018a, p. 1) in

online courses are:

• Items not used are hidden from Course Navigation

• Content is “chunked” into manageable pieces by leveraging modules (e.g. organized by units, chapters,

topic, or weeks)” (Canvas, 2018a, p. 1).

In addition, the CCEC suggests, “Text Headers and indention are included within modules to help guide student

navigation” (p. 2) and “Tables are only used for tabular data” (p. 3) as a best practice that adds value to the course for

learners using mobile devices.

Furthermore, the CCEC directs users to “Visit the Mobile App Design Course Evaluation Checklist

blog post to access

an additional resource!” (Canvas, 2018a, p. 1). The Canvas Course Evaluation Checklist: Mobile App Design

Considerations tool serves as an addendum to the CCEC. Of the eight criteria on the checklist, the following are

indicated as essential and standard design components:

• Text headers are included within modules to help guide student navigation.

• Chunk content into smaller parts (2000 words max) and use the module tool to organize Canvas Pages

into a table of contents.

• When possible, Canvas Pages are used to present content, instead of linking to external URLs or files in

the flow of the module (Canvas, 2018b, pp. 1-2)

In addition, the following are considered “best practice” and add value to online courses:

• Instructions and prompts are platform neutral to minimize student confusion.

• Students are alerted and given alternatives when an unsupported file type is used.

• Assessment design takes into account the additional tools students have when working on a mobile

device - camera, video, audio, file upload, GPS (Canvas, 2018b, p. 1)

The CCEC indicates including the following criteria are “exemplary and elevate learning” (Canvas, 2018b, para. 1):

• Use Requirements within Modules to give users a visual bookmark of their progress.

• Assessment design takes into account the ability for students to use the Mobile Annotations tool on an

assignment that uses an uploaded PDF (Canvas, 2018b, pp. 1-2).

Open SUNY Course Quality Rubric

OSCQR, the evaluation instrument created by the OPEN State University of New York (SUNY) staff and campus

stakeholders, mentions mobile learning in Standard 8, "Appropriate methods and devices for accessing and

participating in the course are communicated (mobile, publisher websites, secure content, pop-ups, browser issue,

microphone, webcam” (Online Learning Consortium, 2019a, para. 1).

This is an author-produced, peer-reviewed version of this article. The final, definitive version of this document can be found online at

TechTrends: Linking Research & Practice to Improve Learning, published by Springer. Copyright restrictions may apply. doi: 10.1007/s11528-

019-00463-6

6

In addition, Standard Eight is explained further on the “Explanation, Evidence, and Examples” page on the OSCQR

site:

• Explore your course on your own mobile device to see which features work well, and which features can

be troublesome (Online Learning Consortium, 2019a, para. 6).

• Ask learners at the end of the term for feedback on their frustrations with technology. This can guide the

information you share out the next time you teach the course (Online Learning Consortium, 2019a, para.

10).

• Include this information in your course welcome video, or create a separate screencast overview video

detailing what devices and access methods will work best in the course (Online Learning Consortium,

2019a, para. 11).

OSCQR has a mobile standards section. The standards in this section state:

• Hyperlinks are provided for embedded content.

• The course avoids the use of tables and multiple levels of indents.

• Text is not placed to the left or right of images.

• When specifying width, percentages are used instead of pixels.

• The course is tested on multiple mobile devices.

• Any apps that are required for students are available on both Android and iOS mobile platforms.

• Efforts are made to minimize the use of content that does not work on mobile devices (such as Flash and

Java).

• When file attachments are necessary, PDF is used as much as possible.

• Content is divided into small, manageable chunks (Online Learning Consortium, 2019b, lines 69-77).

Individual standards are linked to explanations of how instructional design practices justify the standard.

Quality Learning and Teaching Instrument

QLT, the course evaluation instrument developed out of the California State University Office of the Chancellor, is

the only instrument to have a separate section that addresses the accessibility of course content on mobile devices,

although the section is deemed “optional” (California State University, 2019, Section 10). Users are informed, “Not

all course components must be tailored toward mobile devices (e.g., online exams)” (California State University, 2019,

Section 10). The components of this section state:

10.1 Course content was easy to read on multiple platforms such as PCs, tablets, and smartphones.

10.2 Audio and video content displayed easily on multiple platforms such as PCs, tablets, and

smartphones.

10.3 The number of steps users had to take in order to reach primary content was minimized.

10.4 The visibility of content not directly applicable to student learning outcomes was minimized.

(California State University, 2019, para. 2)

Quality Online Course Initiative Rubric

QOCI, developed by the Illinois Online Network, University of Illinois Springfield, addresses design for mobile

devices at two places. First, QOCI indicates, “Scrolling is minimized or facilitated with anchors to improve usability

for desktop and mobile devices” (Illinois Online Network, 2018, p. 5) in the Instructional Materials and Technologies

This is an author-produced, peer-reviewed version of this article. The final, definitive version of this document can be found online at

TechTrends: Linking Research & Practice to Improve Learning, published by Springer. Copyright restrictions may apply. doi: 10.1007/s11528-

019-00463-6

7

section, subheading, “Structure and Design.” Second, in the Accessibility section, QOCI indicates under the

Documents (HTML, Word, PowerPoint, Excel, etc.) subheading, “Content is readable on mobile devices” (Illinois

Online Network, 2018, p. 25).

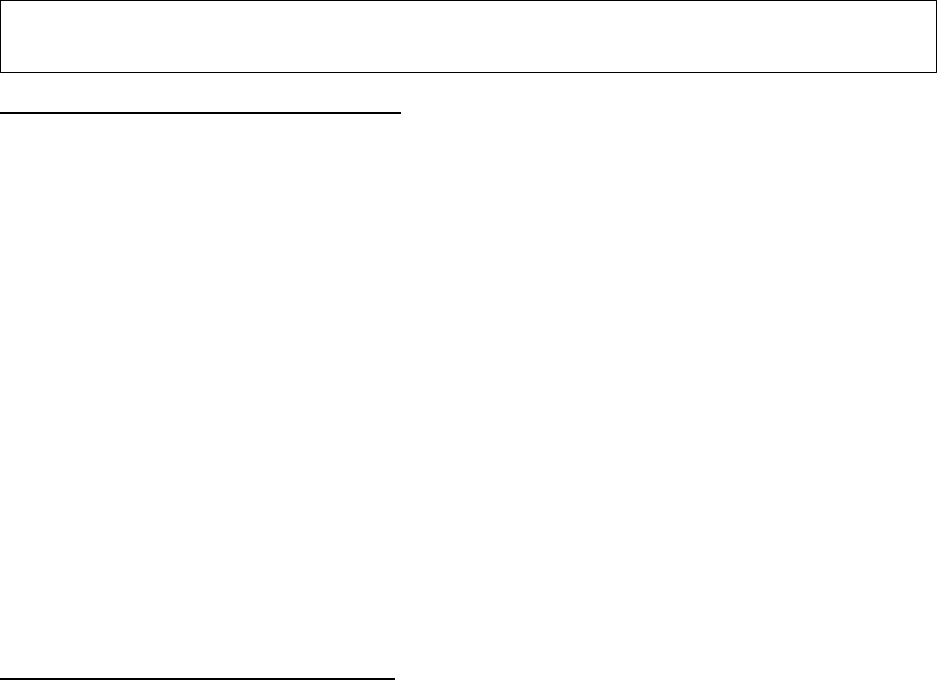

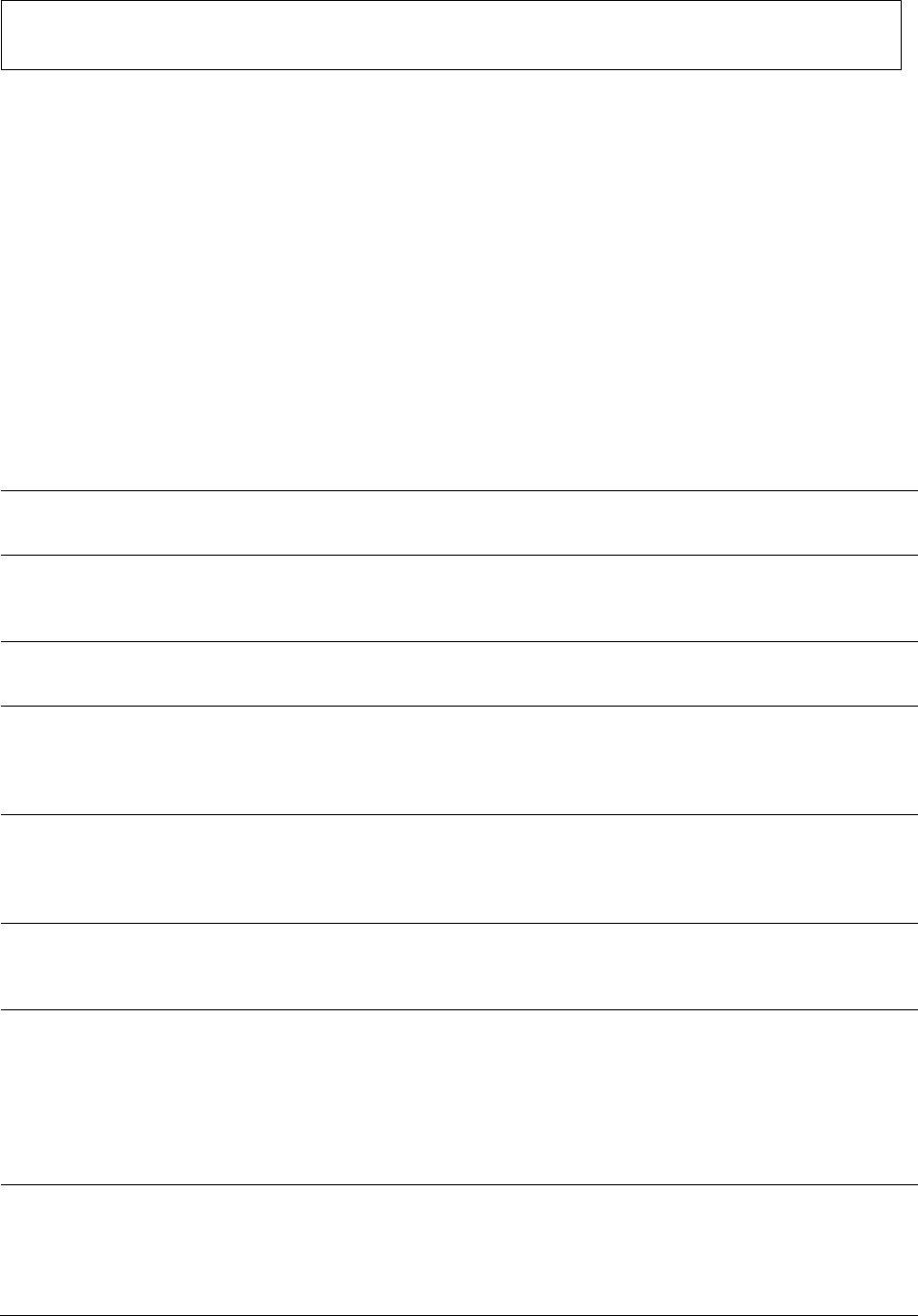

Common Standards in the Rubrics

Among the four online course design evaluation instruments that include standards concerning online course design

for mobile devices, only two common criteria were identified (Table 2).

Table 2

Common Criteria on Evaluation Instruments

Element

CCEC OSCQR QLT

QOCI

Instructor/Course designer should look at the course on a mobile device.

X

X

X

X

Content is chunked.

X

X

Four evaluation instruments (CCEC, OSCQR, QLT, and QOCI) have a common criterion indicating that the user (i.e.,

instructor/course designer) should look at the course on a mobile device (Table 3).

Table 3

Common Criterion on Four Evaluation Instruments

CCEC OSCQR QLT QOCI

“It’s always best practice to

review your course(s) in the

app” (Canvas, 2018b, para.

3)

“The course is tested on

multiple mobile devices”

(Online Learning

Consortium, 2019b, line 73).

“Course content was easy

(California State

University, 2019, Section

10).

“Content is readable

on mobile devices”

(Illinois Online

Network, 2018, p. 25).

In addition, two instruments

(CCEC and OSCQR) have a common criterion indicating that content should be chunked

or divided into manageable chunks (Table 4).

Table 4

Common Criterion on Two Evaluation Instruments

CCEC

OSCQR

“Content is “chunked” into manageable pieces by

leveraging modules (e.g. organized by units, chapters,

topic, or weeks)” (Canvas, 2018a, p. 1).

“Content is divided into small, manageable chunks”

(Online Learning Consortium, 2019b, line 77).

The four evaluation inst

ruments do not share any other criteria to guide the design of online courses for learners using

mobile devices.

This is an author-produced, peer-reviewed version of this article. The final, definitive version of this document can be found online at

TechTrends: Linking Research & Practice to Improve Learning, published by Springer. Copyright restrictions may apply. doi: 10.1007/s11528-

019-00463-6

tablets, and smartphones”

platforms such as PCs,

to read on multiple

8

Discussion

One of the greatest challenges for online course designers “is to ensure that tasks are suited to the affordances of the

devices used” (Stockwell & Hubbard, 2013, p. 3). Earlier in this paper, we showed that mobile devices are used by

the majority of students to access online learning (Galanek et. al., 2018; Magda & Aslanian, 2018; Seilhamer et al.,

2018a); however, well-defined guidelines of how to design online courses for learners using mobile devices are lacking

(Viberg & Grönlund, 2017).

After reviewing the various national and statewide online course design instruments, we were concerned to learn that

students should be “alerted...when an unsupported file type is used” (CCEC; Canvas, 2018b, p. 1) and asked about

their frustrations with technology at the end of the term (OSCQR; Online Learning Consortium, 2019a, para.10). As

one of the QOCI criteria states, content should be readable on mobile devices. Online learning has been heralded as a

way for students to learn anytime, any place. Online learning is appealing to non-traditional students who may need

greater flexibility due to work and family responsibilities (Zawacki-Richter, Müskens, Krause, Alturki, &

Aldraiweesh, 2015). Non-traditional students are more apt to access courses via mobile devices (Galanek et al., 2018).

We need to ensure all students have equal access to learning. This is supported by the Universal Design for Learning

(UDL) guidelines that indicate the importance of changing the environment, rather than trying to change the learner

(CAST, 2019).

The stated purpose of the reviewed national and statewide course design evaluation instruments is to inform/guide

users of best practices and/or improve the quality of online courses. Evaluation instruments that do this by condensing

research-based information into easy-to-understand criteria and provide examples and/or explanations that help to

further guide users serve an important function for online course designers and reviewers. Research indicates that the

majority of students—67 percent according to Magda and Aslanian (2018)—are using mobile devices to access online

courses. Course designers need to be aware of the best practices for designing online courses for all students and

utilize these practices to create successful learning experiences. Designing online courses with consideration of

learners using mobile devices should not be seen as optional or an addendum. It is a critical factor that should be

considered when designing online courses.

Previous research has identified the importance of intuitive navigation, chunked content, and accessibility for all

learners (Baldwin et al., 2018). These criteria are critical for online course design and should be considered by

instructors and instructional designers designing courses for students using desktop/laptop computers and mobile

devices. In addition, it seems essential to establish best practices for designing online courses with the understanding

that students may be using mobile devices. Instructors need to look at courses with a mobile device to understand their

students’ learning experiences better. Based on our research and experience as instructional designers and online

instructors, we suggest the following design tips, which encourage device compatibility, content readability, format

optimization, and mobile-friendly navigation to guide future online course design.

Device Compatibility

• Test the course on multiple mobile devices. This tip comes from four online course evaluation

instruments examined in this paper (CCEC, OSCQR, QLT, and QOCI). Online courses look

different—and may operate differently—depending on the device used (e.g., smartphone,

tablet, or laptop). Optimize every page for mobile delivery. And consider how students hold

their devices to ensure they can view content clearly regardless of their devices’ orientation

(i.e., landscape or portrait; Hoober & Berkman, 2018). If necessary, tell students your course

content works best in a certain orientation.

• Eliminate content that does not work on mobile devices (found in OSCQR). Mobile courses

should be simple to use and avoid software, or applications, that are not mobile friendly (such

as Flash and Java).

• Ensure any applications (“apps”) students need are available on both Android and iOS mobile

platforms (found in OSCQR). Give students the links to the Google Play Store or App Store for

the apps they need in the course.

This is an author-produced, peer-reviewed version of this article. The final, definitive version of this document can be found online at

TechTrends: Linking Research & Practice to Improve Learning, published by Springer. Copyright restrictions may apply. doi: 10.1007/s11528-

019-00463-6

9

• Ensure course directions are applicable for all delivery devices (e.g., smartphones, tablets,

laptops, or desktop computers; found in CCEC and Krull & Duart, 2017). Students may use a

variety of devices, so it is important to offer directions for all delivery modes.

Content Readability

• Divide content into small, manageable chunks. This tip comes from two online course

evaluation instruments examined in this paper (CCEC and OSCQR). Mobile users are

accustomed to consuming material for shorter periods of time. Chunk material on short, easy-

to-read pages. Then group pages in a logical way (e.g., by topics). Eliminate excess words and

make key information easy for students to access to facilitate reading.

• Avoid unnecessary or irrelevant images. Images should be used to support content and not

merely be decorative (QLT). Load times may be longer for mobile devices so it is important to

prioritize content.

• Avoid using tables (found in OSCQR). Tables may not automatically resize to the correct width

for mobile devices, causing users to navigate across and down the content.

• Minimize or eliminate downloads. Portable document format (PDF) are recommended by

OSCQR and by Blackboard (2017a) but PDFs tend to be big and hard to navigate on mobile

devices.

Format Optimization

• Use mobile friendly font sizes and typefaces. Aim for font size 14 pixels to accommodate

mobile users. A larger typeface requires less focus, enhances readability, and provides a

stronger emotional connection (Miller, 2014). Sans serif typefaces (e.g., Arial, Calibri,

Helvetica, and Verdana) are cleaner and easier to read on mobile devices (Bureau of Internet

Accessibility, 2019). To improve legibility and avoid confusion, pick a font and use it

consistently.

• Indent content sparingly (found in OSCQR). Indentation is a good way to draw attention to

items but many mobile devices are too small to display more than one level of indentation

effectively.

• Take advantage of the LMS header styles. Headings add hierarchal structure and organization

to course content (Hoober & Berkman, 2018).

• Use bold for emphasis, rather than italics. Italics are harder to read on mobile devices (Hoober

& Berkman, 2018).

• Specify width in percentages instead of pixels for inline frame elements (i.e., iframes) (found

in OSCQR). Design mobile course content in a way that responds or adapts to the size of the

user’s screen.

• Avoid placing text to the left or right of images (found in OSCQR). Mobile users tend to focus

on the center of the screen. So put the most important information there.

• Provide hyperlinks for embedded content (found in OSCQR). Hyperlinks should describe what

students will see when they click on the link (e.g., “For more information, you can look at this

online course design checklist

.”). Avoid simply stating “click here.” Also, use the Validate

Links in Content tool in Canvas, the Check Course Links tool in Blackboard, or similar tools

in other LMS to ensure that all links work correctly.

This is an author-produced, peer-reviewed version of this article. The final, definitive version of this document can be found online at

TechTrends: Linking Research & Practice to Improve Learning, published by Springer. Copyright restrictions may apply. doi: 10.1007/s11528-

019-00463-6

10

Mobile-friendly Navigation

• Minimize the number of ‘clicks’ necessary to reach content (Rios et al., 2018; Tabuenca et al.,

2015). The three-click rule is an unofficial web design strategy that suggests users should be

able to find the information they seek within three clicks. While this rule is disputed (see

Laubheimer, 2019), it is still optimal to limit the amount of clicks necessary to access key

content and complete tasks.

• Provide clear navigation cues and a roadmap for all users. By simplifying menu choices (e.g.,

eliminating items that are not used or should not be used to navigate directly to an item), users

will be nudged to navigate the course in the manner desired by the course designer (Baldwin et

al., 2018). Provide a quick video at the beginning of the course that shows students how to

navigate the course on all devices. Follow the principles of universal design for learning: when

navigation is simplified for mobile users, all users benefit.

• Reduce scrolling (found in QOCI). This tip relates to chunking materials into manageable

pieces. Many students will not scroll down or not completely scroll down to the end of the page.

On mobile devices, users develop scrolling fatigue (Smith, 2017). As a result, students may

miss or overlook important content that cannot be viewed without scrolling.

• Provide hyperlinked email addresses and phone numbers for student services, LMS help, and

the instructor (Gove, 2019). By offering click-to-connect points within your course (e.g., on the

home page, in the syllabus, and in areas where additional support may be necessary), students

will have access to support as needed.

It may not be optimal—or even advisable—to use mobile devices to take tests, write discussion posts, or draft essays.

But for some students, mobile devices are a lifeline to education. We need to design courses that offer a welcoming

environment to all learners (CAST, 2019).

Conclusion

Mobile learning is student-driven (Attenborough & Abbott, 2018). There is a need for institutions, course designers,

and instructors to acknowledge the use of mobile devices and support learners’ use of these devices to maximize

learning. Increasing the usability of mobile learning—or at least encouraging instructors to look at the design of their

courses on mobile devices—may improve student perception of online courses and increase online learning

satisfaction.

In addition, instructors need guidance in designing online courses. National and statewide online course design

evaluation instruments should help instructors and instructional designers understand the course design elements that

need to be adapted or changed for mobile course design. Researchers and developers of online course design

evaluation instruments can be informed by the gaps identified in this study and possible standards addressing online

course design for learning via mobile devices. Personnel at LMS organizations may use this research to consider ways

to expand technological features that allow responsive designs.

Future research is encouraged to further identify effective online course design practices that are applicable to all

students’ learning needs. Accessing online courses via mobile devices has become commonplace for many college

students. By understanding the strategies necessary to provide quality criteria for online courses, we will be able to

provide a better online learning environment.

This is an author-produced, peer-reviewed version of this article. The final, definitive version of this document can be found online at

TechTrends: Linking Research & Practice to Improve Learning, published by Springer. Copyright restrictions may apply. doi: 10.1007/s11528-

019-00463-6

11

References

Asiimwe, E.N., & Grönlund, A. (2015). MLCMS actual use, perceived use, and experiences of use. International

Journal of Education and Development using Information and Communication Technology (IJEDICT), 11

(1), 101-121

Alexander, B., Ashford-Rowe, K., Barajas-Murph, N., Dobbin, G., Knott, J., McCormack, M., ... & Weber, N.

(2019). EDUCAUSE Horizon Report 2019 Higher Education Edition (3-41). Retrieved from

https://library.educause.edu/-

/media/files/library/2019/4/2019horizonreport.pdf?la=en&hash=C8E8D444AF372E705FA1BF9D4FF0DD

4CC6F0FDD1

Attenborough, J., & Abbott, S. (2018). Leave them to their own devices: Healthcare students’ experiences of using a

range of mobile devices for learning. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning,

12(2), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.20429/ijsotl.2018.120216

Baldwin, S. J. (2019). Assimilation in online course design. The American Journal of Distance Education.

https://doi.org/10.1080/ 08923647.2019.1610304.

Baldwin, S. J. & Ching, Y.-H. (2019). Online course design: A review of the Canvas course evaluation checklist.

The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 20, 3.

Baldwin, S., Ching, Y. H., & Hsu, Y. C. (2018). Online course design in higher education: A review of national and

statewide evaluation instruments. TechTrends, 62(3), 46–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s11528-017-0215-z.

Blackboard. (2017a). Best practices for mobile-friendly courses. Retrieved from

https://www.blackboard.com/Images/MobileBestPractices_FINAL.pdf

Blackboard. (2017b, April 10). Blackboard exemplary course program rubric. Retrieved from

https://community.blackboard.com/docs/DOC-3505-blackboard-exemplary-course-program-rubric

Blackboard. (2018a). Learn 2016 theme. Retrieved from

https://help.blackboard.com/Learn/Administrator/SaaS/User_Interface_Options/Learn_2016_Theme

Blackboard. (2018b). Mobile learn. Retrieved from https://help.blackboard.com/Mobile_Learn

Blackboard. (2018c). What is “ultra”? Retrieved from

https://help.blackboard.com/Learn/Instructor/Getting_Started/What_Is_Ultra

Blackboard. (2019). Compare Blackboard app and mobile learn. Blackboard. Retrieved from

https://help.blackboard.com/Blackboard_App/Compare_Blackboard_App_and_Mobile_Learn

Bogdanović, Z., Barać, D., Jovanić, B., Popović, S., & Radenković, B. (2014). Evaluation of mobile assessment in a

learning management system. British Journal of Educational Technology, 45(2), 231-244

Brightspace. (2018). How do I make the content within my course more responsive? Retrieved from

https://community.brightspace.com/s/article/How-do-I-make-the-content-within-my-course-more-

responsive

Bureau of Internet Accessibility. (2019). Best fonts to use for website accessibility. Retrieved from

https://www.boia.org/blog/best-fonts-to-use-for-website-accessibility

California State University. (2019). CSU QLT course review instrument. Retrieved from

http://courseredesign.csuprojects.org/wp/qualityassurance/qlt-informal-review/

California Virtual Campus-Online Education Initiative. (2018). CVC-OEI course design rubric. Retrieved from

https://cvc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/CVC-OEI-Course-Design-Rubric-rev.10.2018.pdf

Canvas. (2018a, June 29). Course evaluation checklist [Blog post]. Canvas. Retrieved from

https://community.canvaslms.com/groups/designers/blog/2018/06/29/course-evaluation-checklist

Canvas. (2018b, June 29). Mobile app design | Course evaluation checklist [Blog post]. Retrieved from

https://community.canvaslms.com/groups/designers/blog/2018/06/29/mobile-app-design-course-

evaluation-checklist

Canvas. (2018c, October 18). Canvas limited-support guidelines for mobile browsers on tablet devices [Blog post].

Retrieved from https://community.canvaslms.com/docs/DOC-13692-canvas-limited-support-guidelines-

for-mobile-browsers-on-tablet-devices

Canvas. (2019). Canvas mobile users group. UDL guidelines. Retrieved from

https://community.canvaslms.com/groups/cmug

CAST. (2019). Frequently asked questions. Retrieved from http://udlguidelines.cast.org/more/frequently-asked-

questions

Clark, R. C., & Mayer, R. E. (2016). E-learning and the science of instruction: Proven guidelines for consumers and

designers of multimedia learning (4

th

ed.). San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons.

This is an author-produced, peer-reviewed version of this article. The final, definitive version of this document can be found online at

TechTrends: Linking Research & Practice to Improve Learning, published by Springer. Copyright restrictions may apply. doi: 10.1007/s11528-

019-00463-6

12

EDUCAUSE. (2019). Mobile learning. Retrieved from https://library.educause.edu/topics/teaching-and-

learning/mobile-learning

Edutechnica. (2019, March 17). LMS data-Spring 2019 updates [Blog post]. Retrieved from

https://edutechnica.com/2019/03/17/lms-data-spring-2019-updates/

Galanek, J. D., Gierdowski, D. C., & Brooks, D. C. (2018). ECAR study of undergraduate students and information

technology, 12. Retrieved from https://tacc.org/sites/default/files/documents/2018-

11/studentitstudy2018_0.pdf

Gove, J. (2019). What makes a good mobile web site? Google Developers. Retrieved from

https://developers.google.com/web/fundamentals/design-and-ux/principles/

Han, I., & Shin, W. S. (2016). The use of a mobile learning management system and academic achievement of

online students. Computers & Education, 102 (2016), 79-89.

Hoober, S. & Berkman, E. (2018). Designing mobile interfaces: Patterns for interaction design. Sebastopol, CA:

O’Reilly Media, Inc.

Hsu, Y. -C., & Ching, Y. -H. (2012). Mobile microblogging: Using Twitter and mobile devices in an online course

to promote learning in authentic contexts. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed

Learning, 13(4), 211–227.

Hu, X., Lei, L. C. U., Li, J., Iseli-Chan, N., Siu, F. L., & Chu, S. K. W. (2016). Access Moodle using mobile phones:

student usage and perceptions. In D. Churchill, T. Chiu, J. Lu, & B. Fox (Eds.), Mobile Learning Design

(pp. 155-171). Singapore: Springer.

Hwang, G. J., & Tsai, C. C. (2011). Research trends in mobile and ubiquitous learning: A review of publications in

selected journals from 2001 to 2010. British Journal of Educational Technology, 42(4), E65-E70. doi

http://doi.dx.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2011.01183.x

Illinois Online Network. (2018). Quality online course initiative. Retrieved from

https://uofi.app.box.com/s/afuyc0e34commxbfn9x6wsvvyk1fql8p

Jaggars, S. S., & Xu, D. (2016). How do online course design features influence student performance? Computers &

Education, 95, 270-284.

Joo, Y. J., Kim, N., & Kim, N. H. (2016). Factors predicting online university students’ use of a mobile learning

management system (m-LMS). Educational Technology Research and Development, 64(4), 611-630.

Kleen, B., & Soule, L. (2010). Reflections on online course design-Quality Matters™ evaluation and student

feedback: An exploratory study. Issues in Information Systems, 11(2), 152-161.

Kobus, M. B., Rietveld, P., & Van Ommeren, J. N. (2013). Ownership versus on-campus use of mobile IT devices

by university students. Computers & Education, 68, 29-41.

Krull, G. & Duart, J. (2017). Research trends in mobile learning in higher education: A systematic review of articles

(2011 – 2015). International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 18, (7).

https://doi.org/10.3991/ijim.v8i4.3991

Laubheimer, P. (2019, 11 August). The 3-click rule for navigation [Blog post]. NN/g Nielsen Norman. Retrieved

from https://www.nngroup.com/articles/3-click-rule/

Lee, D. Y., & Lehto, M. R. (2013). User acceptance of YouTube for procedural learning: An extension of the

technology acceptance model. Computers & Education, 61, 193-208.

Legon, R. (2015). Measuring the impact of the Quality Matters Rubric™: A discussion of possibilities. American

Journal of Distance Education, 29(3), 166-173.

Liu, I., Chen, M.C., Sun, S. Y., Wible, D. & Kuo, C. (2010). Extending the TAM model to explore the factors that

affect intention to use an online learning community. Computers & Education, 54(2), 600-610.

López, F.A. & Silva, M.M. (2014). M-learning patterns in the virtual classroom. Mobile Learning Applications in

Higher Education [Special Section]. Revista de Universidad y Sociedad del Conocimiento (RUSC), 11 (1),

208-221. doi http://doi.dx.org/10.7238/rusc.v11i1.1902

Magda, A. J., & Aslanian, C. B. (2018). Online college students 2018: Comprehensive data on demands and

preferences. Louisville, KY: The Learning House.

Maryland Online, Inc. (2014, September). Quality Matters overview. Retrieved from

https://www.qualitymatters.org/sites/default/files/pd-docs-PDFs/QM-Overview-Presentation-2014.pdf

Miller, X. (2016, 29 September). Your body text is too small [Blog post]. Medium. Retrieved from

https://blog.usejournal.com/your-body-text-is-too-small-5e02d36dc902

Mödritscher, F., Neumann, G., & Brauer, C. (2012, July). Comparing LMS usage behavior of mobile and web users.

In 2012 IEEE 12th International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies (pp. 650-651). doi

http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/ICALT.2012.42

This is an author-produced, peer-reviewed version of this article. The final, definitive version of this document can be found online at

TechTrends: Linking Research & Practice to Improve Learning, published by Springer. Copyright restrictions may apply. doi: 10.1007/s11528-

019-00463-6

13

M

oodle. (2019). Creating mobile friendly courses. Moodle. Retrieved from

https://docs.moodle.org/37/en/Creating_mobile-friendly_courses

Online Learning Consortium. (2019a). OSCQR–Standard #8. Retrieved from https://oscqr.org/standard8/

Online Learning Consortium. (2019b). The open SUNY course quality review OSCQR (version 3.1). Retrieved

from https://oscqr.org

Quality Matters. (2018). Specific review standards from the QM higher education rubric, sixth edition. Retrieved

from

https://www.qualitymatters.org/sites/default/files/PDFs/StandardsfromtheQMHigherEducationRubric.pdf

Rios, T., Elliott, M., & Mandernach, B. J. (2018). Efficient instructional strategies for maximizing online student

satisfaction. Journal of Educators Online, 15(3), 158-166.

Seilhamer, R., Chen, B., Bauer, S., Salter, A., & Bennett, L. (2018a, April 23). Changing mobile learning practices:

A multiyear study 2012–2016. EDUCAUSE Review. Retrieved from

https://er.educause.edu/articles/2018/4/changing-mobile-learning-practices-a-multiyear-study-2012-2016

Seilhamer, R., Chen, B., deNoyelles, A., Raible, J., Bauer, S., & Salter, A. (2018b). 2018 Mobile survey report.

University of Central Florida. Retrieved from

https://digitallearning.ucf.edu/msi/research/mobile/survey2018/

Shin, W. S., & Kang, M. (2015). The use of a mobile learning management system at an online university and its

effect on learning satisfaction and achievement. The International Review of Research in Open and

Distributed Learning, 16(3), 110-130.

Smith, A. (2018, September 13). How scrolling can make (or break) your user experience. UsabilityGeek. Retrieved

from https://usabilitygeek.com/how-scrolling-can-make-or-break-your-user-experience/

Stockwell, G., & Hubbard, P. (2013). Some emerging principles for mobile-assisted language learning. The

International Research Foundation for English Language Education, 1-15.

Tabuenca, B., Kalz, M., Drachsler, H., & Specht, M. (2015). Time will tell: The role of mobile learning analytics in

self-regulated learning. Computers & Education, 89, 53-74.

Viberg, O. & Grönlund, A. (2017) Understanding students’ learning practices: challenges for design and integration

of mobile technology into distance education. Learning, Media and Technology, 42(3), 357-377.

https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2016.1088869

Wilcox, D., Thall, J., & Griffin, O. (2016, March). One canvas, two audiences: How faculty and students use a

newly adopted learning management system. In Society for Information Technology & Teacher Education

International Conference (1163-1168). Savannah, GA: Association for the Advancement of Computing in

Education (AACE).

Zawacki-Richter, O., Müskens, W., Krause, U., Alturki, U., & Aldraiweesh, A. (2015). Student media usage

patterns and non-traditional learning in higher education. The International Review of Research in Open

and Distributed Learning, 16(2) 136-170.

This is an author-produced, peer-reviewed version of this article. The final, definitive version of this document can be found online at

TechTrends: Linking Research & Practice to Improve Learning, published by Springer. Copyright restrictions may apply. doi: 10.1007/s11528-

019-00463-6